In November 2015, Billy Frank Jr. was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor:

Billy Frank, Jr. was a tireless advocate for Indian treaty rights and environmental stewardship, whose activism paved the way for the “Boldt decision,” which reaffirmed tribal co-management of salmon resources in the state of Washington. Frank led effective “fish-ins,” which were modeled after sit-ins of the civil rights movement, during the tribal “fish wars” of the 1960s and 1970s. His magnetic personality and tireless advocacy over more than five decades made him a revered figure both domestically and abroad. Frank was the recipient of many awards, including the Martin Luther King, Jr. Distinguished Service Award for Humanitarian Achievement. Frank left in his wake an Indian Country strengthened by greater sovereignty and a nation fortified by his example of service to one’s community, his humility, and his dedication to the principles of human rights and environmental sustainability.

From Where the Salmon Run (download free here):

Billy Frank Jr. took his first breath on March 9, 1931, six days after President Herbert Hoover signed “The Star-Spangled Banner” into law as the national anthem. One day, Billy would defend his country; then he’d spend a lifetime challenging the nation to rise to its ideals.

…

One day in the winter of 1945, as the temperature hovered in the mid-forties, Billy Frank Jr. became a fighter. Along the Nisqually River, Billy pulled thrashing and squirming steelhead and dog salmon from his fifty-foot net. To avoid the keen eyes of game wardens, he’d set his net in the river the night before. The downed branches of a fallen maple covered his canoe perfectly. But in the stillness of those early-morning hours, as he diligently butchered the chum, a yell pierced the silence. For Billy, life would never be the same.

“You’re under arrest!” state agents shouted with flashlights in hand.

“Leave me alone, goddamn it. I fish here. I live here!” Billy fired back.

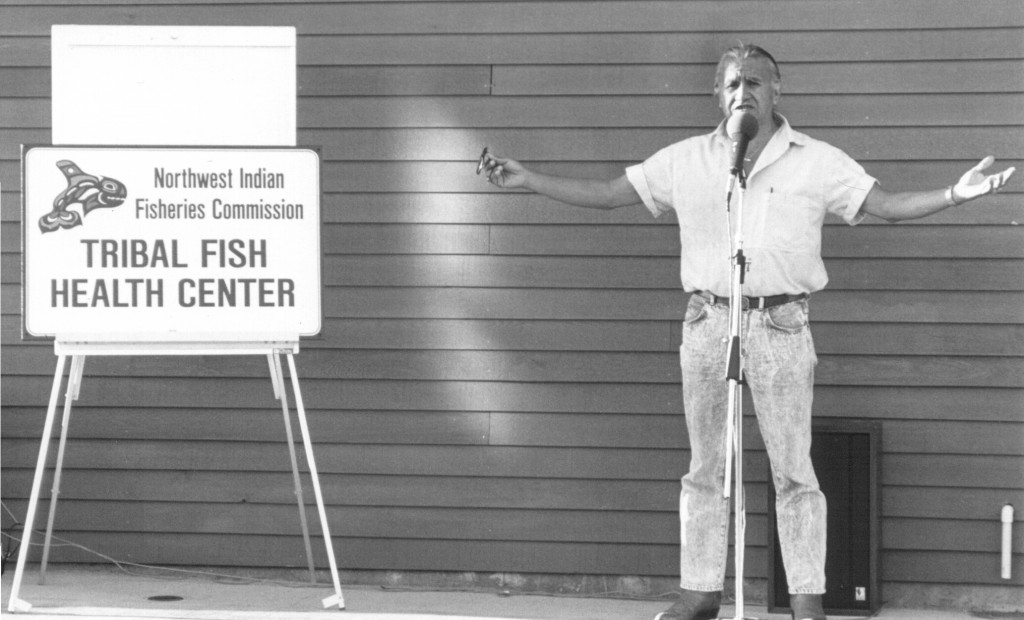

Billy Frank Jr. at the dedication of the NWIFC’s fish health lab:

Beginning with his first arrest as a teenager in 1945 for “illegal” fishing on his beloved Nisqually River, he became a leader of a civil disobedience movement that insisted on the treaty rights (the right to fish in “usual and accustomed places”) guaranteed to Washington tribes more than a century before. The “fish-ins” and demonstrations Frank helped organize in the 1960s and 1970s, along with accompanying lawsuits, led to the Boldt decision of 1974, which restored to the federally recognized tribes the legal right to fish as they always had.

For years, the state of Washington regarded the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek as an irrelevant nuisance. The state insisted that it could impose its fishing regulations on the tribes, notwithstanding the treaty. It tried to do so forcefully, destroying property and making hundreds of arrests. But the traditions and training passed on to Billy Frank Jr. by his father – which in turn were taught to him by Billy’s grandfather, and on into the past – were ingrained. The tribes had given ground and shed blood over the years, but they were determined

to fight for what was rightfully theirs.

Billy Frank was first arrested in December 1945, when he was just 14. More than 50 arrests would follow over the years, as they would for many other tribe members. Billy’s formal education ended when he finished 9th grade at a junior high in nearby Olympia, but continued in the company of his fellow fishermen. He worked construction by day – mostly highways and sewers – and fished by night, suffering occasional rough treatment, arrest, and confiscation of his precious gear.

In 1952, at age 21, Frank fulfilled a dream and joined the Marines. He was proud of his two years in the corps, but in 1954 he returned to his roots – fishing and the six acres of trust property along the river that his father had acquired in 1919.

With arrests and strife between tribal fishermen and state fish and game officials continuing in Washington, on September 18, 1970, the Justice Department filed suit in United States v. Washington. The suit asked for declaratory relief for treaties covering areas west of the Cascade Mountains and north of the Columbia River drainage area, including the Puget Sound and Olympic Peninsula watersheds.

The case was assigned to Judge George Hugo Boldt (1903-1984), a tough law-and order jurist. The trial began on August 27, 1973. Judge Boldt held court six days a week including on the Labor Day holiday.

Forty-nine experts and tribal members testified, among them Billy Frank Jr. and his then-95-year-old father.

The decision in United States v. Washington, 384 F.Supp. 312 (1974), issued byJudge Boldt on February 12, 1974, was a thunderous victory for the tribes. The treaties were declared the supreme law of the land and trumped state law. Judge Boldt held that the government’s promise to secure the fisheries for the tribes was central to the treaty-making process and that the tribes had an original right to the fish, which the treaty extended to white settlers.

It was not for the state to tell the tribes how to manage something that had always belonged to them. The tribes’ right to fish at “all usual and accustomed grounds and stations” included off-reservations sites, as well as their diminished lands. The right to fish extended not just to the tribes but to each tribal member.

Following the Supreme Court’s upholding of the Boldt decision in 1979, the NWIFC and the state had to determine how they were going to co-manage the fisheries they shared jurisdiction over. A long process of creating co-management guidelines and establishing trust between the tribes and state officials began with the development (of the) Puget Sound Salmon Management Plan in the early 1980s. With Frank at the helm, the NWIFC established working relationships with state agencies and other non-Indian groups to manage fisheries, restore and protect habitat, and protect Indian treaty rights.

Billy Frank was honored with countless awards for his decades-long fight for justice and environmental preservation. They include the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Common Cause Award for Human Rights Efforts, the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism, the American Indian Distinguished Service Award, the 2006 Wallace Stegner Award, and the Washington State Environmental Excellence Award.